|

StoryTIME | ||||

| ||||

|

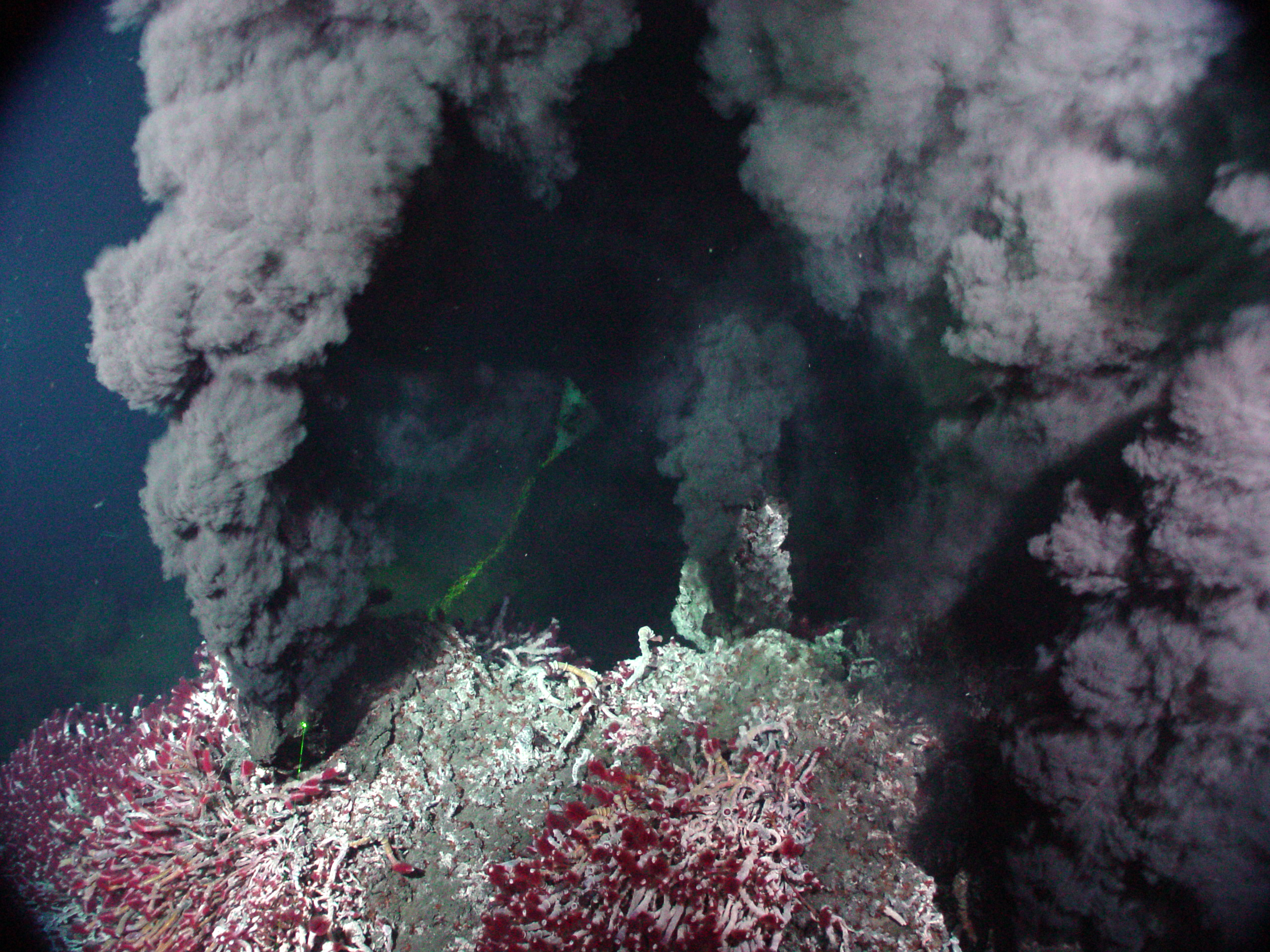

Submarine field expedition

by Amanda Bates 12.05.2020 After reaching the seafloor on the Endeavour segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge 200 km off the west coast of Vancouver Island in the human operated vehicle Alvin, we spent a very focused morning searching for a vent called “Hot Harold” to sample fluids thought to exceed 350ºC. The time ticked by as we circled through a maze of chimney formations, my list of tasks feeling heavier and heavier on my lap as we searched without success. It was a relief when we finally located the vent, obtained our water samples, and then moved on to our next task.

Amanda Bates @AmandaEBates ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

The strange incident with the giant clam

by Maria Dornelas 19.05.2020 This stretch of the reef between South and Palfrey Islands feels like home. I have been coming here almost every year for the past 12 years. I can draw the contour of the reef crest with my eyes closed. I can tell you in excruciating detail how many species of coral there are here, and how rare or abundant they are. I mostly have my head in the coral when I am here, but I have seen sharks and turtles around. There are rumours of dugong sightings, and photographs of manta rays. But my favourite story about the reef we call Trimodal is about a giant clam. We started calling this reef Trimodal, because of the species abundance distribution of the corals on this reef crest. We counted over 42 thousand coral colonies there in 2005, and the SAD had a funny shape with three modes. I can’t remember why exactly, but on this occasion we decided to park the boat in the lagoon area, at the back of the reef. We looked for a patch of sand and rubble and dropped anchor. We got our gear on and I braced myself for the swim across the reef flat towards the crest where we were more likely to find the species we were looking for. Because we were anchoring rather than using the mooring we normally used, we checked the anchor before we swam across. This is always a good idea, as coming back from a dive to find your boat gone is not much fun. Much to our surprise as we looked down, we saw that a giant clam had caught our anchor chain and closed up.

The clam was not willing to let it go, so we decided to carry on with our job, and deal with the anchor on our return. At least the boat was definitely not going anywhere. It was a beautiful sunny day, and I didn’t even complain much about the long swim. One of my legs is slightly longer than the other because of a motorcycle accident I had when I was 18. You probably won’t notice if you know me, and Ionly notice when I am swimming with my fins on. It makes long swims always interesting. In the British sense. We got on with our job. Eventually, we were done for the day and headed back to the boat. By then the giant clam had decided the anchor chain was not tasty and had let it go. We headed back with a full day of data and an interesting story. In the literal sense. Maria Dornelas @maadornelas ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Seagrasses - unsung heroes!

by Jon Lefcheck 26.05.2020 Seagrasses are the underappreciated heroes of coastal ecosystems. As heroes, seagrasses are vital nurseries for many species of fishes and invertebrates, contribute roughly one-fourth of global fisheries production, and store as much carbon as some terrestrial forests! But they are sometimes lost in the public eye: a recent scientific study has shown that of all ecosystems on planet Earth, seagrasses have the fewest songs written about them, fewer than marshes, bogs, or even steppes (can you think of a song that you listened to that mentioned the word ‘steppe’ in it? Well, turns out it appears in 36x more songs than the word ‘seagrass!’) So, it is my great pleasure to publicize the humble seagrass, and the valuable services they provide. Beyond the services mentioned above, seagrasses are vital to the coastal ‘food web.’ They host a wide array of small and tasty critters, including small shrimps and crabs, that are essentially ‘fish food’ for the many species that utilize seagrass beds at some point in their lives. Which is why our group has been monitoring these animals—and the things that eat them—in their seagrass habitat for 15 years at a place called Goodwin Island, at the mouth of the York River Estuary in Chesapeake Bay, USA. This study has generated thousands of samples and taken dozens of dedicated scientists, students, and citizens to collect and process. Chesapeake Bay is notable for a lot of reasons—it was, of course, the site of the first British colony in the Americas at Jamestown…ok, well, the first reasonably successful one—but what a lot of people don’t know is that it is one of the most dynamic environments on the planet. I have seen icebergs float by on the river in the same year I have sat in water approaching 35°C (that is as warm as, if not warmer than, your bathwater). Working in such a place presents a unique set of challenges.

Jon Lefcheck @jslefche ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

The life of a transect tape

by Rick Stuart-Smith 02.06.2020 Laying out a transect line over the reef becomes one of those things you no longer realise you are doing – you hit the bottom, tie it off and start swimming. But when you turn to start the survey, your brain switches on again, and on coral reefs, can overload while trying to jot down the names of everything swimming in the vicinity of the line. Trying to recount the amazing marine life seen along reef transects can be hard to do justice. So many good memories. Instead of the usual tales of mantas, whales and endangered red handfish, this time I’ve stopped to consider the life of the transect line itself. This 50-m long piece of flattened fibreglass goes through more than most people crunching the numbers at the other end would imagine.

Transect line attack by marine life has never prematurely ended a survey though, that I know of. Anthropogenic disturbance is more serious, and has resulted in abandoned surveys, wasted effort, air and time. Regardless of how isolated a site may seem, other dive groups can sometimes show up. A few times I’ve been swimming along the line to meet a stranger coming back towards me reeling in my line. Who knows if they thought they were cleaning up some rubbish or thought they could use the line for something themselves. But once a situation like this escalated into what was almost my only underwater fight. Surveying a deeper, high current site with only just enough air to safely do the survey and finish the dive promptly, I met a dive guide followed by group of less-than-expert divers. We were on a coral reef, and he had been stripping up my transect line off the reef and had made a huge tangle out of it. He was waving his arms around at me and pointing at the reef, presumably indicating that he thought the line had been damaging the reef, while beneath him the big tangle he had generated in the line was tearing a bit of soft coral as he was aggressively tugging the line up, and behind him his dive group were crashing around the reef like bulls in a china shop. Regardless of his good intentions, the mess he made took me a very long time to sort out on the bottom, fighting the current and watching my air running down. No data could be collected from that site, which was very hard to get to and became a wasted opportunity. So next time you are using reef survey data, instead of only thinking about the diverse array of fishes and invertebrates represented by the numbers, spare a thought for the charismatic macro-equipment that we all rely on! Rick Stuart-Smith @RickStuartSmith ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

A thrilling and scary encounter

by Samanta Iop 09.06.2020 From 2008 to 2010 I worked on a large remnant of the Atlantic Forest in southern Brazil. This incredible area contains the largest longitudinal waterfall in the world, the ‘Salto Yucumã’ (meaning “big falls” in indigenous language), with about 2 kilometers of extension in the Uruguay river. It is also home for many threatened animal and plant species, including the iconic tropical jaguar and the beautiful jararacuçu, a large viper with a powerful poison.

Most days this job was peaceful and pleasant - though utterly exhausting as we would walk a minimum of 8 kilometers every day. Each day a different animal fell into the traps and filled us with joy and excitement. But in one lazy, rainy day, things took an unexpected turn with a bizarre plot-twist. I woke up as usual, had breakfast with my field colleagues and got prepared to start another morning of pitfall trap inspection. Eventually, my team and I had to acknowledge that we couldn’t locate two of the trails, despite the fact that we had been successfully finding them for the last 6 months. Shame on us! However, we didn’t give up and this paid off as we finally managed to find the trails. But that’s not all. It suddenly began to rain torrentially, and we found ourselves in a hurry to move forward and finish the inspection of the traps. When we were on the last trail, we decided to leave unnecessary equipment such as thermos bottles and backpacks on the road to pick up on the way back, this would make the task of walking through the dense forest trail easier and allow us to finish the job more quickly. As we reviewed the traps, we shared the impression that there was something, or someone, around us. A subtle, but powerful presence. “We need to keep up with work because the rain doesn’t look like it’s going to stop, come on team!” I remember someone saying that. As we walked back to the road to pick up our stuff and head to the accommodation, that powerful presence seemed to be following us, somehow observing, inspecting us from a few metres apart, just as we had been doing with the animals in the pitfall traps. “Keep moving guys, rain is getting heavier!”, someone said as if we were afraid of the rain at that moment! Finally, on the road to pick up our things, I looked at the ground and noticed huge footprints all around the thermos and backpacks we had left there. So, I looked across the road towards the trail entrance, and I saw the silhouette of a huge animal getting engulfed by the forest. My heart raced. Excitement was making my breath run out. It was that iconic, endangered carnivore species. If we still have had some doubts, the fresh footprints confirmed it: our silent secret admirer was a jaguar. We had been so close to each other, and for a considerable amount of time! I tried to recall what the survival manuals say about close-range encounters with a jaguar: run? Stay still? Shout out loud? I could not remember anything. An adrenaline rush took over my body. Maybe the jaguar was as scared as we were, and fortunately didn’t see us as a threat. We did not think twice: we gathered our belongings and left the road in a hurry towards our accommodation. There we dried ourselves off and shared our feeling for having lived such an incredible experience. But the thrilling experience left a permanent marker, as we have been known to good-humoured local residents as "the biologists who fled the jaguar" since then

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

King without a crown: bowing to snakes in the Thai jungle

by Felipe Serrano 16.06.2020 The before nearby voices of my colleagues of the Sakareat Conservation and Snake Education Team were now only getting dimmer and dimmer. “I am getting behind”, I thought. It probably was due to having to navigate through streams, slippery fallen logs and thorny bushes. It could also be due to only knowing those Thai evergreen forests for about a month now. It was only when I heard the growl that I realized that it most likely had something to do with the 2.5 kg and nearly 3-meter King Cobra I was carrying in a box. The King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) is the longest venomous snake in the world, ranging from India to China, and it feeds mostly on other snakes such as the Reticulated Python, the longest snake in the world. For those who have not been lucky to hear it, its growling hiss is somewhere between an alert Rottweiler and the heavy breathing of a certain masked black-dressed lightsaber-wielding space father

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Love comes from the sea!

by Viviana Brambilla 23.06.2020 For someone doing a PhD on coral ecology while based Scotland, fall fieldwork in the Tropics is a real game changer. The chance of longer daylight and sunshine lifts the mood and gives us the vitamin D boost we need to face Scottish winters. Fieldwork is what you look forward to the most, since day 1. Or, at least, that is how I feel. In my fieldwork, I joined a team of marine biologists and engineers to collect data for my research and survey coral reefs around Lizard Island in Australia. Every year we spend about a month at the research station on the island, collecting data for producing 3D maps of reef sites and identifying all the fish and corals we find around our maps. There are so many stories I could tell about how human behaviour changes during those long trips – you could say people loosen up a lot and maybe even lose their mind a bit – but I want to focus on animal encounters, which are the very gems of fieldworks. One year, 2017, was particularly strong in those encounters. Maybe animals couldn’t be bothered to hide after 2 years of coral bleaching and would rather just be on-your-face most of the time. Anyway, that year we had a few episodes worth of mention. For example, a juvenile fish shoal decided to take shelter in the space between our legs while we were working underwater. We ended up with a bunch of inappropriate close-ups of our groin area in wetsuit just to have a picture of those tiny little fish. But out of all that happened that year, today I chose to tell a (n interspecific) love story. That day, we had a team three (co-PIs Maria and Josh, and I) and we were heading to survey the corals of our northernmost site with the boat the research station assigned us. Josh was on driving duty, Maria was sitting on his side back in the stern, and I was on the bow, enjoying a PI-free ocean view.

Viviana Brambilla @viv_brambilla ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

On the Edge

by Fritha West 02.07.2020 Standing at the top of Hermaness, peering down at a raft of puffins below me, I wonder how much further I can creep forward. The edge here is rocky and sandy, and it’s hard to know where to put my feet as the ground slopes slowly but surely towards hundreds of meters of sheer cliff below. At least it isn’t raining, I tell myself. When it rains here the grassy fescues and sedges become as slick as ice. A dry day, windy or not, is as rare as it is welcome in the Shetland Isles.

It’s a strange feeling. Almost dreamlike, to be standing so close to such a huge drop. 200m of crumbling gneiss above crashing waves. And the winds here rival hurricanes, the air feels solid when it hits you. I don’t get vertigo- I usually pride myself on having a head for heights - but as the gusts pick up again and lurch me forward, I almost cry out in panic. Staggering back and swearing quietly under my breath, I glance around for another team member, someone to share my close shave with. But they are all walking their own transects, the other side of the cliffs. I am alone, just me, and a nearby bonxie, watching me keenly. I shake my head and lift my binoculars, recommencing the count. 2 meters now feels a little too close. Paper link: Fritha West ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Me, a delicatessen for groupers?

by Daniel Gomez Gras 17.07.2020 To divers, the Medes islands of the Spanish Mediterranean are a veritable paradise. Located in the upper-right corner of the Iberian Peninsula, this group of seven islets are teeming with life, which attracts thousands of marine adventurers per year. The Medes are where I did most of my PhD fieldwork, and where I had some of the most magical (and strange) moments I have experienced as a marine ecologist.

Friendly, that is, most of the time.

When we spotted the wall, I pulled out the sampling bags from my carrier bag. To my surprise, five massive groupers came straight to me. I gave them a friendly greeting, much as a human can greet a fish; however, I soon realized they weren't just coming to say "Hi". They were coming for me!

I remembered titan triggerfish attacking divers in Mabul island (Malaysia) to protect their brood and thought that maybe the groupers were just doing the same. My immediate reaction was to kick off horizontally into the blue to have some distance from the wall. However, the groupers continued to chase me and kept trying to swallow all the bags around my hands in a vicious feeding frenzy. The water was speckled with bits and pieces of my sampling bags. That's it, I thought, the sampling is over. Fortunately, Ignasi, who seemed to be less tasty for the groupers and managed to avoid the frenzy, was more level headed and signed for me to hide the bags. In my initial confusion, I had pushed my hands with the bags away from my body to protect the diving gear (and my vital organs). But Ignasi had realized that the groupers were just interested in the bags, so maybe hiding them against the chest would do the trick. And it worked! The bags were likely just the same size, colour, and shape as the fish they normally eat. Or maybe someone used to illegally feed the groupers from bags that looked like ours. In any case, the groupers stopped attacking me as soon as the bags were out of sight. We could even get back to the wall and finish sampling. "I thought the sampling was over," I confessed to Ignasi when we were back on the boat. "At first, I thought that too," he replied, "but then I thought how quickly we would have been sent back to the water if we had told our supervisor Cristina that we couldn´t finish the sampling because of the groupers". I laughed, he was right. Daniel Gomez Gras @danigomezgras ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

The joys of unexpected field work

by Claudia Faustino 30.07.2020 How does one study vultures? In my case, I got lucky and got access to an untouched dataset. Then, I got a weeks notice for a fieldwork opportunity in Namibia, which I enthusiastically took. I knew very little about vultures when I first went, and I will never forget the experience. My PhD project used data collected from satellite-based tags attached - with care, by our experienced field colleagues — to the back of the vultures. Back in St. Andrews (where I live and study, in Scotland), I analysed the data to see how vultures move and interact with their environment. As exclusive scavengers, vultures do the vital work of keeping the environment free of rotting carcasses, and are as such considered "ambassadors" of ecosystem health. Nonetheless, their populations have been declining steeply mainly due to food shortages and mass poisoning. Some people never get to experience how their research data is collected, but I got lucky. When the opportunity to do a two-week stint in the field came up, I jumped on a plane to Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. There, all the field equipment, collected by the lead researcher – a wildlife vet – along with my clothes and food supplies were packed into an awesome four-by-four SUV. My first job was to drive the supplies ~600 miles to Bwabwata National Park, our field site. The field work also required a plane and so the lead researcher was to join me two days later having flown a two-seater plane there himself! How cool is that! Navigating through an unfamiliar country, on bumpy gravel roads, in +30ºC, and without AC was challenging. I needed two days to complete my drive, so I stopped to overnight at the farm of another fieldwork volunteer. The morning that I left he was tending to his cattle, and later that day he drove up to help with tagging vultures.

The fieldwork consisted mainly in setting a baited trap, waiting for hours under the shade, and eventually rushing to the trap to release the bird – a definite rush of adrenaline! During this fieldwork, I also got to hold a vulture for the first time in my life. These are hefty birds with a strong beak and, as scavengers, they certainly didn't smell great. Overall, the fieldwork was a success. We saw plenty of vultures, and managed to tag three. I was grateful for field colleagues who could fly planes, and those that managed to solder broken equipment in a rush. If you get the opportunity for field work in Namibia, even if it's short notice, my advice is you take it.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

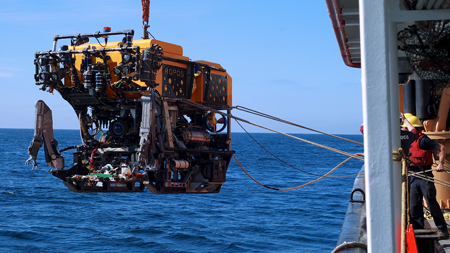

Deep Sea Research Without Experience

by ematveev@mun.ca 11.08.2020 Here’s how I got to do deep-sea research in my undergrad.

I was lucky in that I got a unique research experience during my undergrad, when I was fully unqualified. After taking a project-based course with Dr. Sally Leys, I started working in her lab as a research assistant. Sally's lab is based at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Canada) and predominantly studies sea sponges (Porifera), what these animals can teach us about the evolution of multicellularity, and their functional ecology. As a research assistant, I participated in lab meetings and listened to the planning of a research cruise set to explore the sponge reefs off the coast of British Columbia (Canada). On a ship, surrounded by the open sea, studying the deep unknown? It sounded like the aspiring marine biologist's dream, but I knew that room was restricted to graduate students and PIs. Nevertheless, I never failed to mention how desperately I wanted to come; always "joking", but not really. One week before the ship set sail, one of the graduate students sadly fell ill. To my own disbelief, I was invited as a last-minute replacement. I hopped from a plane to a zodiac, and on to the Canadian Coast Guard Ship The Vector. I was assigned a bunk and a 12-h shift, like everyone else. The ship had a Remotely Operated Vehicle called ROPOS (ropos.com) on board. This is a roughly van sized robot decked out with over $2M in cameras, thrusters, instruments, and two WALL-E like arms which are linked to on-board mini-arm controllers. Using these hyper-precision arms, the crew can place our 1-cm diameter instruments into a 2-cm diameter sponge opening.

As the ROV descends, the water goes from teal to black. Squid, ctenophores, jellyfish, chaetognaths, and countless other animals float past on the way down. At 150 m below, the lights beam down on an expanse of sponges, far as the robot eyes can see, teeming with life. This deep, sponges have no algal symbionts, and are a ghostly pale complexion. Their rigid silica (aka "glass") skeleton, allows them to tower high over the sea floor. It’s truly an alien sight. The reefs off the coast of British Columbia and Alaska are the only extant sponge reefs so far known; it's likely a globally unique ecosystem. Not only do they filter vast amounts of water, but the nooks and crannies of their exhalent openings provide a home to diverse species, like rockfish, squat lobsters, prawns, and octopus. After this first accidental cruise I was invited to come on two more, each time accumulating more experience and responsibility. Six years later and I'm still analyzing the days-worth of flow and respiration data we collected. My advice to undergraduate level biologists would be to let people know what you want, and hope for the best.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Stuck Between Land and Sea

by Damaris Torres-Pulliza 14.09.2020 My fieldwork days as a scientist started at the rim of volcanoes; from there, my career path slowly meandered towards the water. It took me down slopes, passed through caves, watersheds, urban areas, agricultural lands, and coastlines. But before reaching the ocean, I got stuck – quite literally – at the interface between the land and sea. Back in 2008, I joined fieldwork efforts to characterize the mangrove forest structure and diversity in the north Pacific coast of Costa Rica. One beautiful sunny morning, after checking our gear and confirming that the tide was receding, we entered the Iguanita mangrove forest. For five hours we worked our way through the tangle of roots, going deeper and deeper into the forest. So far, everything was going according to plan. Our team leader made the call — "we have finished!"— and the plan was to backtrack our way to the entrance. But, at that point, we were quite far from the entry point, it was hot, the chaotic root system was cruel, the mosquitoes were unrelenting, and our water supply was running low. We heard breaking waves in the distance, so we knew the beach was nearby. A new, seemingly better, plan was hatched; we would head towards the beach and walk back along the sea.

Two of us went forth first, and within the blink of an eye ended up waist-deep in the mud. What just happened? My first thought was of an old Robot Chicken cartoon where a giraffe sinks in quicksand and goes through the "five stages of grief". Would that be me? What to do? We were utterly stuck and likely sinking. Then, I thought of the tide slowly rising above my head. And then, crocodiles. What is it with the mind playing tricks on us? As a child, I had nightmares with crocodiles, even if we don’t have them in Puerto Rico, where I'm originally from. But what got me worried wasn’t my irrational fear, but the look of the two locals scanning the area, seemingly worried. I didn’t ask why, I just knew we needed to get out of there. At that point, I realized I had 'Pablo' the walking stick with me. Finally, my thoughts got useful: I just needed to follow the "Man vs. Wild" instructions. That is, to lay Pablo across the surface and use it to push myself up. It was working! I kept using 'Pablo' until I reached the roots at the other side of the ditch and dragged myself out. I passed 'Pablo' around, and everybody got out - distinctively ungracefully. The only casualties were several boots that stayed in the mud and were lost forever. At last, we reached the beach, and we went straight for a swim. The plume of mud coming out from our clothes reached the surfers floating in the distance. All refreshed, relieved, and feeling silly, we got to answer questions from the curious people around. We briefly explained that we were studying the mangroves and why. They looked interested, and added, "Pura Vida, just be careful, there are crocs around"! Luckily, I got to continue my career path across the land-sea interface into coral reefs ecosystems. Coral reefs have proved to be another quite adventurous fieldwork realm, and my true passion. All of this, thanks to trusty 'Pablo', my first #fieldmascot.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

You are but mortal, says the whinchat

by Will Cresswell 25.09.2020 I have a picture of this small drab-looking bird, a whinchat, right above my office desk. As I look up from my computer it stares me down, like the servant hired to whisper "you are but mortal" to temper the ego of newly crowned Roman emperors. This whinchat is the one that got away. The bird I couldn’t recatch, no matter how hard I tried. No matter how inventive I was.

Catching just any bird is easy. Catching a specific bird, and indeed one that you have already caught, is not. Individuals learn to avoid your traps and nets very quickly. We get around this with the whinchats by using a variety of trapping methods. I’ve become very good at it, but some birds seem uncatchable a second time. Last November in Nigeria, I tried to catch this winchat on six separate days, in six different ways. I had already caught all the other tagged whinchats, and on my last day in the field I pulled out all the stops. I set up all my nets the afternoon before, crisscrossing its little wintering territory to intercept all the flight lines I had observed it using in my previous attempts. To lure the winchat into a false sense of security, I rolled up the nets so they couldn’t catch anything and let the bird fly around and get used to them. When furled, the nets pose no danger to the birds. The next morning, I got up two hours before sunrise, and stealthily unrolled the nets, ready for capture. I was back out of the territory well before first light and hid nearby. It was a perfect setup, I just needed to wait for the window of half-lit dawn when a whinchat patrols its territory, but the nets are still invisible. But, just as the timing was perfect, a man shuffled along the path towards the territory. He stopped dead in the centre, obviously oblivious to my beautifully invisible nets. He pulled out a pack of cigarettes, lit up, dropped his trousers and settled in for ten minutes of important morning bowel movements. I watched in horror as my whinchat was completely put off by this, and relocated into a neighbouring territory. The man finished, and wandered off, none the wiser. The moment was gone. You can be in the right place, at the right time, but sometimes shit happens.

Will Cresswell ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Snake encounter in the Trinidad Bush

by Amy Deacon 07.10.2020 Imagine you’ve insisted on bringing a young research assistant into the "bush", despite their parents' trepidation. Now imagine a venomous snake is swimming towards said research assistant. Not good. I spent 5 years as a postdoc working on the initial BioTIME project, monitoring patterns of diversity in Trinidad's Northern Range. This meant returning to the same stretches of stream several times a year to sample fish, aquatic invertebrates, and diatoms.

While fish could be identified on site, identifying smaller samples meant hours of sifting through petri dishes. Thankfully I had the expertise and company of Sarah, a fantastic graduate research assistant. One day, Sarah casually mentioned that she had never visited ANY of the Northern Range rivers. I was horrified that she hadn't experienced the beauty of the places where all of our samples come from, and insisted that she accompany us on an upcoming trip. She was keen, but the "bush" is considered dangerous by many Trinidadians, and her parents needed some convincing. We persuaded them that she was in good hands with our experienced team.

Now, Trinidad and Tobago have nearly 50 species of snake, and only 4 of these are dangerously venomous. Reassuring statistics, you'd think. Unfortunately, the most venomous species, the fer de lance (Bothrops atrox), is defended well enough to be assertive and is therefore most commonly seen. I couldn't believe it; in years of sampling and literally hundreds of field trips, the one time we encounter a venomous snake is when Sarah has joined us for the first time!

Fieldwork in Trinidad is always an adventure. I'm sure that's a big part of why, a decade after embarking on BioTIME sampling, I am still here, exploring the island's incredible biodiversity and enjoying the adventures that each day brings. Amy Deacon @amy_e_deacon ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

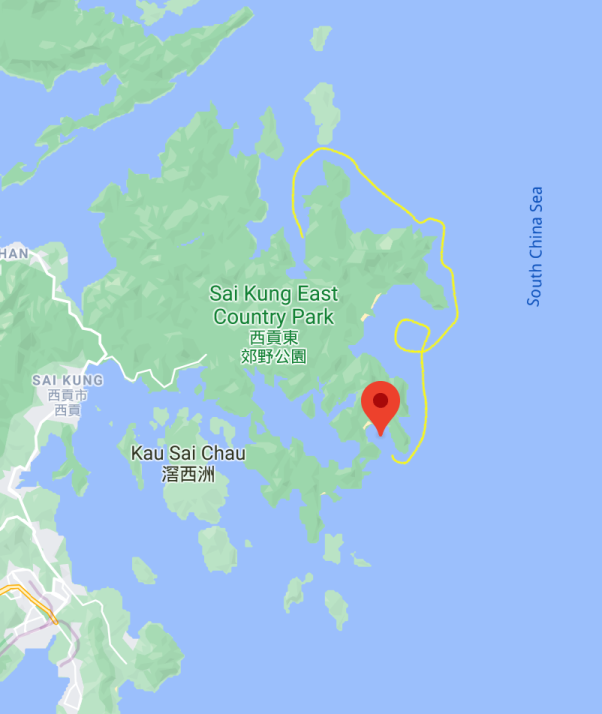

Trial by... fog

by Cher Chow 21.10.2020 In February 2019 I was part of a team conducting reef fish biodiversity surveys in Hong Kong. This was essentially a two-year field season filled with long days, often spent sopping wet in isolated areas. Conditions I’m sure are relatable to many biologists. While most of our survey sites were easily accessible from the city’s piers, some required a 40-minute speedboat ride along the rocky coastline of a towering UNESCO Geopark. Despite the longer commute and tricky navigation, these were some of my favourite sites to dive at because the steep cliffs usually meant finding more interesting critters and fish. Our survey days had two dives: one at noon, and another 1 hour after sunset. On the night dive that we were wrapping up our dry season, we had to tackle one of those tricky survey sites, called Long Ke. Our skipper, Ze Fu (姐夫), was one of what we call "water people" in Cantonese— a multi-generational skipper and fisher. He expertly navigated around the craggily shallows of the coastline, even in the dark.

The way back to the dive centre was perilous even without the fog, but now visibility was limited to two meters in front of the boat. We strapped our dive torches to our wrists, pointed them outwards, and slowly navigated back. The light beams on the speedboat scattered in the fog and it was all a greyish blur.

Somewhere along the first rocky bay past Long Ke, I realised Ze Fu was going in a circle, despite my instructions to tell him to go northeast. My dive buddies were looking on port and starboard to keep a lookout with their torches in case more mounts would come up again, and they noticed that Ze Fu was going opposite of my directions. He was reading his marine compass wrong. One of my co-workers, Jeffery, realised this and started translating my directions into "left" or "right" instead. But Ze Fu was mixing those up too! Jeffery and I solved this by placing ourselves at port and starboard and used us as directions to make sure Ze Fu didn’t get confused anymore. The slow and improvised navigation teamwork continued for who knows how long. Exhausted, cold, and hungry, we finally made it to the dive centre. It was more than an hour since we surfaced, and I have never been more sure of my navigational skills since then...

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Three birds in the net are worth tears and sweat

by Claudia Tapia Harris 28.10.2020 Everyone that's done fieldwork remembers that day; the one where everything goes unexpectedly perfectly. For me, it happened during the last fieldwork season of my PhD. For over three years now, I've been studying the non-breeding ecology of a long-distance migratory bird, the Common Whitethroat Sylvia communis. As part of my project I spent the last three winters doing fieldwork in Jos, Nigeria; a far cry from the cold, harsh winters of Scotland, where I study. In a way, I became a migratory being myself, and it taught me to fully appreciate the benefits of long-distance migration.

To track the birds, we attach light-sensitive geolocators to the birds' backs. These collect times of sunrise and sunset, and because these times vary depending on where in the world you are, we can infer latitude and longitude positions. However, retrieving this data is easier said than done; one needs to re-catch the same bird to remove the geolocator. As Will Cresswell, my PhD supervisor and author of a BioTime anecdote a few weeks back, wrote: "Catching just any bird is easy. Catching a specific bird is not". Oh, how true, and even more so after they've flown over 10,000 km to Europe and back! Needless to say, getting a geolocator back is an accomplishment worthy of celebration.

When I came back in January, the birds were exactly where I had left them. We decided to go all in, and set up an intricate maze of over 10 nets (each 12 meters long), planning to outsmart them once and for all. It was one hour after sunrise, and we hadn’t even finished setting up the last net when, suddenly, my colleague Arin yelled: "We caught them! And guess what…!?"— I imagine there are no words to describe my face when he told me that we had not only caught our two target birds, but also a third tagged bird that we had not even detected yet! To be honest, it took me a minute or two to actually believe him. It was thrilling. All the tears, the sweat, the roller coaster of emotions, and the sleepless nights had been worth it. It was just the boost that I needed after a long period of not being able to catch any other tagged bird. By the end of the season, after over three months, we managed to retrieve seven geolocators, so you can imagine what these three geolocators in one morning meant in terms of data, and my happiness. Fieldwork is full of magical moments. Of course, many things never go as planned. Things rarely happen the way you imagine them to but sometimes, just once in a while, you will have that one day when everything turns out unexpectedly perfectly.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Bears, Bombs and Belugas

by Ellen Garland 2.11.2020 Killer mud, Grizzly bears, deadly tides, and unexploded ordnances—such challenges are all part of the rich tapestry of fieldwork experiences. However, as a marine biologist studying beluga whale vocalisations, these were not exactly on my list of expectations. A few years ago, I was a postdoc at NOAA's Alaska Fisheries Science Center, investigating population-level differences in Alaskan beluga vocal repertoires. At the time, I had never seen a beluga in the wild – clearly, that's less than ideal in terms of understanding your animal. So when I was lucky enough to be invited for fieldwork aiming to tag critically endangered Cook Inlet beluga whales, I jumped at the chance to observe these critters up close and personal.

Unfortunately, the grassy flat we hiked across was also the firing range for a nearby military base. There is nothing quite like arriving at the parking spot, making lots of noise to scare away the Grizzly bears (!?!), and then hiking 45 minutes across a firing range…in waders….at 5 am. But don't worry, they say, just "stick to the 1 m wide path, it's been cleared of unexploded ordnances". At least on the flats you could see the bears coming.

Then there was the mud. Oh, the mud. A 10 m tide creates a steep 10 m bank down the river edge, and the mud acts like quicksand. At low tide we had to switch over the acoustic gear as it became exposed above the water, which was a race against time. We took safety very seriously as people die in this mud; they get stuck, the tide comes in fast, and they drown.

Sadly, we did not get a tag on a beluga that year, though we got so close on one occasion. I even crawled on my belly—appropriately army style—to get to the water's edge and film the tagging attempts without alerting the beluga to my presence. It was a privilege to watch pods of belugas swim past, observe their behaviour and hear them communicating with each other. They are remarkable creatures, and this window into their world helped me understand them better.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

The modern-day Snow White would be an ecologist

by Dagmar der Weduwen 20.11.2020 In 2017-18, as soon as I’d wrapped up my undergrad exams, I started working as a research assistant with Edinburgh University’s Phenoweb team, studying phenological mismatch in blue tits. I would drive up and down the A9, from Edinburgh to Tain, and spend my days wandering the Scottish Highlands catching birds and counting caterpillars at our 44 field sites. I meandered through rolling fields and along rivers, serenaded by the echoing calls of songbirds and pheasants. Rabbits and hares jumped out of my path, great stags cautiously sneaked up behind me, and owls flew from their perches as I raised them from their slumber. I saw my first red squirrel, and my first golden eagle. But the best part of the work was the blue tits.

My time with Phenoweb fanned the embers of my research interest into a full-blown fire. I realised I loved the long hours of fieldwork, the 10,000-steps-before-lunchtime distances, and traipsing from nest-box to nest-box before driving to the next site. I even loved the dozens of small injuries: the car doors slammed into my knees, stinging nettles clamped between my legs, having ticks cover my skin and clothes, ankles twisted, and, on one occasion, there were even piglet bites. But the moment that really sealed the deal—one that made me realise I wanted nothing more than to spend the rest of my life researching animals— is one I will never forget.

Dagmar der Weduwen @DJWeduwen ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Eavesdropping on whales

by Franca Eichenberger 01.12.2020 "Why would someone dedicate years to studying the humpback whale song?" you may ask. Well, in short, the allure of mystery. Unlike Dory from 'Finding Nemo', we sadly don’t speak whale, so—even though we've known that humpbacks sing for 50 years—we're not entirely sure what the 'lyrics' mean. We do know it's the males that sing, and they do so during breeding season; so, it likely serves an important function in reproduction. Humpback whales stand out from other singing animals in the song's complex structure, constant evolution, and high conformity within a population. In other words: the song progressively changes each year, but all males within a population know the same version, and learn the new changes.

In my project, I'm trying to understand whether some males sing better (or, different) than others, and, if so, whether females prefer to mate with males that sing in a particular way. I joined a team of researchers at IRD (UMR Entropie) and Opération Cétacés to conduct fieldwork on a humpback whale population breeding in New Caledonia (a tiny French island to the east of Australia) during the austral winter (June – September) of 2018.

The sea was calm, offering a glimpse into a foreign world beneath and unveiling the full length of a humpback whale swimming alongside us. It was gigantic, yet its body moved effortlessly, seemingly weightless through the water. As the whale came to the surface to breathe, the wind blew its exhaled air towards me, scattering little whale blow droplets all over my face. My initial unwitting – and, in hindsight, rather stupid – thought was one of pure joy. I have been graced by the moist breath of a whale! I later learned that whale breath can transmit diseases and parasites to humans, and consequently held my breath and turned away from incoming whale showers thereafter. On my second day, the sea was rougher yet I was no less excited. We dropped our hydrophone in the water hoping to hear some whales sing. Lucky for us, the ocean was full of high-pitched shrieks, harmonic cries, and rumbling groans. It was an underwater orchestra – but for whom and why? While I was listening to this exhilarating concert in the middle of the choppy sea, pondering about these questions, a marine-mammals' scientist's worst fear was brewing: I started feeling terribly seasick. While everybody else was enjoying their lunch with the view of two minke whales circling our boat, I was fighting the strong urge to empty my stomach contents over the side rail. However, even with face against the dirty boat floor and the world spinning around me, I still felt like I was the luckiest person on earth.

------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

There's No 20-20 Foresight In a 2020 Field Season

by Valesca de Groot 07.12.2020 Oh, beloved fieldwork. A chance to get our hands a little dirty, and reconnect with the beautiful nature that inspires and fuels our work. And, of course, shy away from that eternally frozen manuscript draft on our monitors. But, fieldwork has its own challenges: sometimes it’s gusting winds, others, a peculiar absence of the target species; or heck, sometimes there’s a global pandemic. My master’s thesis, supervised by Dr. Amanda Bates at the Memorial University of Newfoundland (Canada), uses a new method of examining field metabolic rate in fish through their otoliths (auditory bones). By combining this metabolic rate measure with field methods, I try to predict survival in overwintering juvenile Atlantic cod exposed to increasingly cold winters. As COVID-19 (perhaps you’ve heard of it) spread to the point of a global emergency, I was in the midst of starting an exciting collaboration with Dr. Clive Trueman at the National Oceanography Center (Southampton, UK). A few weeks before “it” went down, I flew to the UK with 326 otoliths and 163 vials of ground Atlantic cod tissue. But not two weeks into my two-month trip I had to leave my samples behind and return to Canada.

Valesca de Groot @ValescadeGroot ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

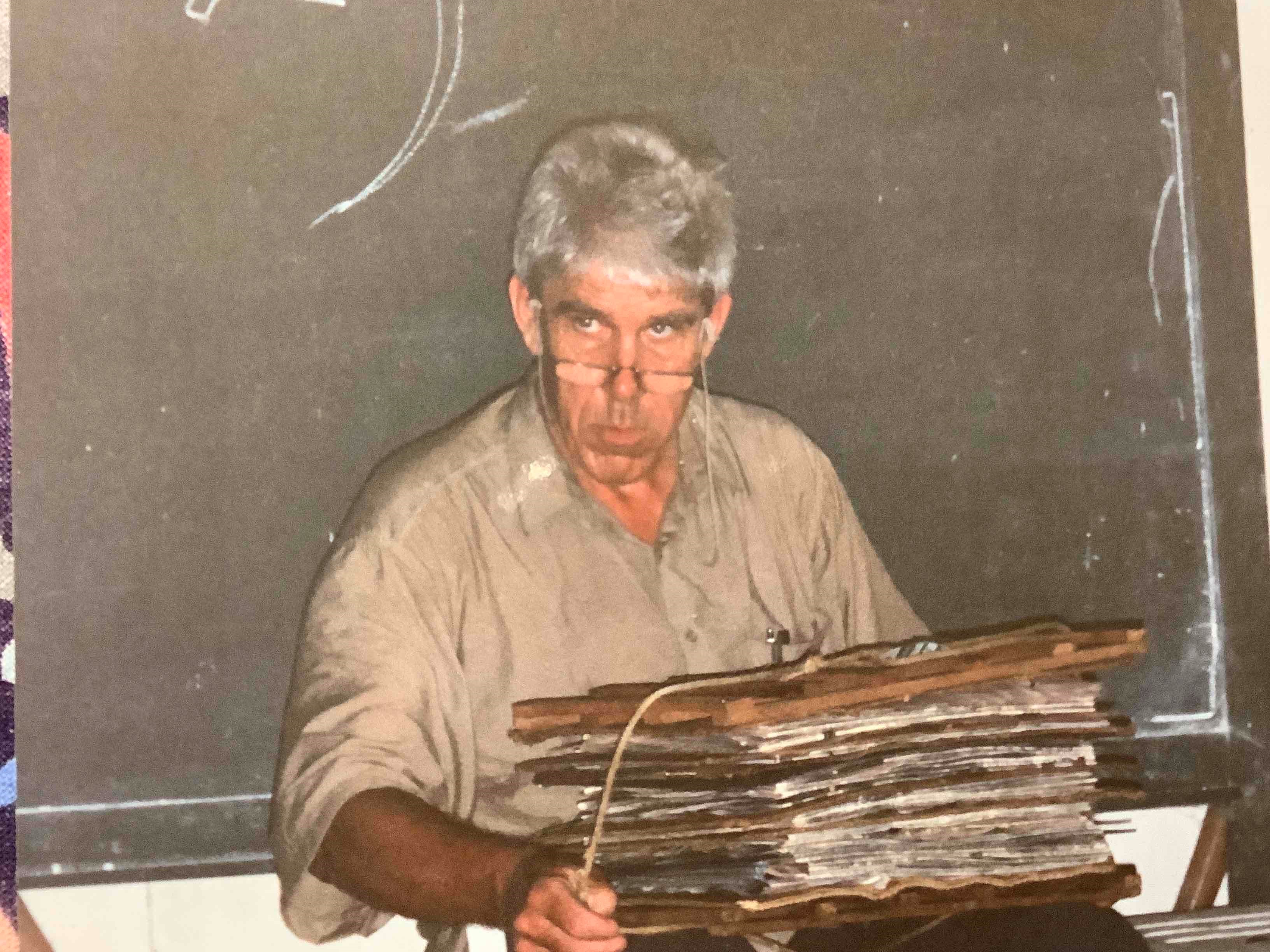

Song for the Trees

by Markus Eichhorn 17.12.2020 Tok Sumpeh is a hard man to find. His family are shifting cultivators in the midst of a Malaysian rain forest, living in a set of temporary huts called ‘pondoks’. Every few years they clear a patch of forest to grow the edible cassava root. Once harvested, they relocate and the forest is allowed to grow back. There is no mobile phone reception, no electricity, no running water; once in the forest, you are entirely cut off from the modern world. My directions were to follow an unmarked trail due north, and expect that someone would meet me along the way. Just before dawn, taking advantage of the relatively cool temperature, I collected my heavy pack and machete and headed into the forest. It was the middle of fruiting season and breakfast was easy to collect along the way. After a few hours’ hike a small Chewong man silently emerged from the foliage. He led me to the rest of my research group and, although we moved at twice my normal speed, it was almost nightfall by the time we reached Tok Sumpeh’s pondok.

Not long after falling asleep I was woken by another song. As one of the few remaining shamen of the Chewong, it is Tok Sumpeh’s responsibility to sing a ritual chant to the forest spirits at night. Each species of tree has its own spirit, so when fruit, fuel, or building materials are collected, the respective spirits need to be thanked. When a tree is in flower, or has fallen down, or simply hadn’t been seen for a long time, these daily observations become part of a direct dialogue between forest and shaman. As he intones, his wife lies beside him muttering reminders. I tried to pay attention, but the repetitive pattern of the song had me drifting back to sleep. But at around midnight I was woken again, just as the moon was rising above the line of trees. This time, Tok Sumpeh’s song had a different message. I lay silently as he asked the spirits to welcome the outsiders who had arrived to count the trees, and to assist us in our work. Although I hold no religious or spiritual beliefs, this was one of the most moving moments of my life. I gained a small insight into what it meant to have one’s life genuinely embedded in the natural world, living alongside countless generations of ancestors watching from the trees.

Thanks to the Chewong, particularly Tok Sumpeh, Tok We and their families; my former PhD student Saifon Sittimongkol and MRes student Jonathan Moore; and the Insitut Biodiversiti Krau for enabling the research. Photo credits are to Saifon Sittimongkol Markus Eichhorn at Trees in Space and @Markus_Eichhorn ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Reflections on the flooded forest

by Anne Magurrann 17.12.2020

At night I could hear the river dolphins hunting fish in the water below us, while in the mornings I watched the caiman and pirarucu as I drank tea on the deck of the floating house. I have been to Mamirauá Reserve in the Brazilian Amazon a number of times now, working with Helder Queiroz and Peter Henderson on its fish diversity, but that initial sense of being somewhere special has stayed with me. Mamirauá Reserve, and the Institute that runs it, is a great example of conservation in action as it supports the sustainable development of the people who live there while documenting and protecting the organisms on which they depend. It demonstrates that solutions that support both people and nature are possible.

Anne Magurran ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

My Hipster Lockdown (before it was cool)

by Kyle Zawada 17.12.2020 My first lockdown was in 2015, but back then I wasn’t avoiding people like we are today. Crammed in a small library with our field crew, some wine, and an emergencies-only bucket, we were avoiding… Nathan. During the first year of my PhD I went to Lizard Island, on the Great Barrier Reef. The goal was to mark every coral colony on a reef previously mapped out by collaborators from Sydney University. The data would later be included in the BioTime database.

Daunting as coral ID was, “Nathan” was a bigger problem. One week into our surveys, a cyclone warning had been raised for the north-east coast of Australia. Cyclone Nathan—or Nay-no as the Aussies on the team nicknamed it— was shaping up to be a force to be reckoned with. This was bad news for the survey team: if Nathan struck Lizard Island, the reef was highly likely to be damaged. At first, we tried going out as often as possible to maximize data collection, but eventually we had to stop due to choppy conditions. Then we found out that Nathan was going to make landfall sometime within the next 48 hours.

Most buildings on the research station are made of wood and are raised off the ground; pretty much the opposite of a cyclone bunker. With no way to escape, we had to cram into the few brick buildings at the station that could withstand the anticipated 170 kph winds. Our team was assigned to the library, where we brought in our mattresses, food (well, snacks and cheese), board games, and anything else we'd need over the next three days (wine, lots of wine). We were also given a bucket. There were toilets 50 m from the library that we could use provided that the storm wasn't too dangerous, and it even had a guide rope to hold on to for safety. But if it was too dangerous, there was the bucket. Between us, we vowed that it would be a 'bucket of last resort' and was only to be used if the other toilets had been thoroughly destroyed in the storm. With the pact in place, we locked down and waited for the storm to pass. After three days of lockdown, we emerged unscathed to find the research base intact but in disarray. Sand was everywhere. Trees uprooted. Even a few boats were overturned. But overall, the damage to the station was minimal. The corals were not so lucky. Where branching and table corals dominated prior, only a handful of boulder colonies remained. Coral cover at the site dropped from 90% to around 10% overnight. During my PhD, Lizard would experience two bleaching events following Nathan, bringing further losses of coral cover and changing the shape of the reef for years to come. However, there has also been some good news since. Although we didn’t finish our surveys, we still managed to map out more than 10000 coral colonies and over 150 species: a massive undertaking. During the following years, my coral ID skills improved dramatically, and in 2019 we saw glimpses of hope for recovery with high numbers of recruits and juvenile corals.

Footnote - Believe it or not I would again be locked down when myself and many of the same team members caught in a hurricane in Hawaii when writing up my PhD thesis, a story for another time. Kyle Zawada @KyleZawada ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

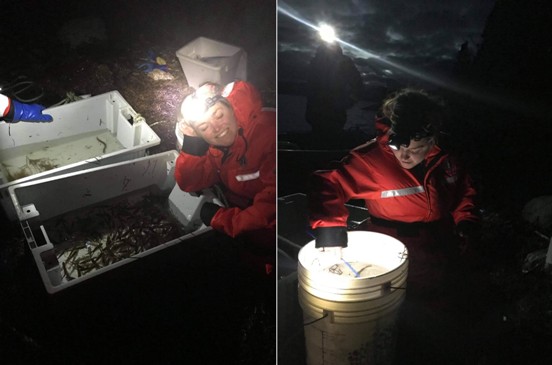

Plankton sampling at North Stradbroke Island

by Claire H. Davies and Anthony J. Richardson 26.03.2021 The ocean is fickle, and there’s no such thing as a typical sampling trip. Some days, the rain lashes my face as the small boat pitches and sways, slowly lurching towards a mooring site blinking in and out of view behind the waves. I manoeuvre the boat to prevent the swell from ruining our plankton sample, struggle to balance while tying a bowline in the net rope, and hold onto a student who admitted to getting seasick a little too late. But other days, sampling trips are a marine biologist’s dream. One calm sunny day, we set off for a mooring site five nautical miles away from North Stradbroke Island, close to Brisbane, Australia. This is one of the Integrated Marine Observing Systems (IMOS) National Reference Stations (NRS); one of seven national mooring sites sampled monthly since 2009 for zooplankton and diverse environmental variables. What are zooplankton? Imagine spending your life suspended in a dense fluid, not mobile enough to overcome the will of currents. That’s about the life of zooplankton. Most are tiny, but some –like the 40 m long siphonophore— are the longest marine animals alive. Zooplankton diversity is staggering, and they represent an important thread in the food web that connects algae to larger animals, like fish. By repeatedly measuring both zooplankton and diverse environmental conditions, we try to understand how some of the smallest animals on earth are affected by changes in the environment.

Claire H. Davies and Anthony J. Richardson @IMOS_AUS with the IMOS plankton team – Frank Coman, Ruth Eriksen, Felicity McEnnulty, Anita Slotwinski, Mark Tonks and Julian Uribe-Palomino ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||||

|

Field work in parallel worlds

by Amelia Penny 26.05.2021

| ||||

|

||||

| Like the desert after the rain, the Ordovician was a time of incredible change. There was sustained increase in marine invertebrate diversity and ecological complexity, which had profound implications for the subsequent history of life. Among the ecological upheavals of this time was a striking change in the composition of reef-building communities. The communities of microbes, sponges and problematica which had been the world’s reef-builders for millions of years were joined by large, robust reef-building animals including corals and bryozoans. We had come to Utah to understand the early stages of this transition. | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

As we clambered up scree slopes, measured sections, and examined reefs, I imagined what this place was like before tectonic movement, sea level change and evolution altered its character completely. The reefs are preserved as rounded limestone mounds, packed with the ghostly-looking fossils of sponges and enigmatic sponge-like organisms called calathids, as well as fragments of other invertebrates: gastropods, trilobites, echinoderms, and brachiopods. I imagined the thousands of little sponges, the size of dinner rolls, and the ancient seawater which flowed through their pores; the gloopy microbial communities everywhere, and the trilobites roving around it all, as dark and purposeful as London taxis. But desert life constantly intervened– from the sudden buzz of a rattlesnake, to the massive, snaking root systems of the tiny juniper trees, high up on the scree slopes, often only half-alive but waving tufts of foliage on upraised branches.

Amelia Penny ------------------------------------------------------------------ | ||

|

Penguins, penguins everywhere!

by Guilherme Bortolotto 04.06.2021 Working in Antarctica was more than a dream-come-true for me; it was a time to look back. Fieldwork on the “ice continent” can feel very lonely sometimes, and not because it’s the least populated place on Earth. As a matter of fact, nobody goes to fieldwork completely alone there. It’s too dangerous. More so, it is the loneliness of being away from family, surrounded by such a beautiful and completely alien landscape, virtually untouched by people. That combination made me think a lot about everything that happened for me to get there.

Guilherme Bortolotto @BortolottoGui ------------------------------------------------------------------ |